The lower Oder valley was best known for its birds. 160 breeding bird species were counted in the German part of the International Park alone, as well as 54 mammal, 6 reptile, 11 amphibian and 49 fish species. In the lower Oder valley, in addition to the black stork and the eagle owl, all three types of eagle (white-tailed eagle, spotted eagle, osprey) breed. Significant are the Black Tern, White Bearded Tern and White-winged Tern, which regularly breed here, as well as the strong corncrake population and the last breeding pairs of Sedge Warbler in Germany. Among the mammals, the otters and the rapidly spreading beaver should be mentioned in particular.

Until the early 1990s, the fauna in the lower Oder valley had not yet been systematically recorded. There have been individual observations for a hundred years, but only a few summarizing representations. In particular, experts from the Mönne (near Stettin) and Bellinchen (Bielinek) nature conservation stations have carried out investigations in their areas that also affect the lower Oder valley.

Above all, the diverse bird life was the special interest of early naturalists such as Paul Robien. In the Brandenburg section of the lower Oder valley between Hohensaaten and Gartz, ornithological research began in 1965 with the work of the Dittberner brothers. It is primarily thanks to this ornithological pioneering work that it was possible to designate larger nature reserves in the Lower Oder Valley as early as the GDR era. It was the ornithologists in particular who laid the foundations for the national park and the waterfront program.

As part of this program, a maintenance and development plan was drawn up for the entire project area. This included the first large-scale and systematic, mostly qualitative recording of selected groups of animals suitable as indicator species. In addition to macrozoobenthos, land snails, spiders, grasshoppers, dragonflies, ground beetles, wild bees, large butterflies, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals were recorded. For the first time, this gives a good overview of the outstanding faunistic importance of this region.

- Kingfisher

- Black stork

- Short-eared Owl

- Crane with chick

- White-tailed eagle

- Corn Crake

The results for the most important animal groups are presented below.

![]()

Macrozoobenthos

The macrozoobenthos, i.e. the small invertebrates of the water bodies more than two millimeters in size, are well suited and widely used indicators for the monitoring and assessment of water bodies. Their suitability for indicators results from the sometimes very narrow habitat requirements of these species. This applies to both the water quality and the morphological design of their habitats. The close habitat connection of many species of macrozoobenthos results in the excellent suitability of this group for the formulation of nature conservation goals within the framework of a maintenance and development plan.

Samples were taken from 30 sample sites typical of the area on four dates in 1995, with the help of a manual collection net and by brushing the underside of floating leaf plants. In addition, flying insects were caught with strip nets and light traps, the larvae of which could not be clearly identified.

- Mantle snails graze on the sunken oak leaf

During the study period, a total of 242 species were identified and 32,000 individuals were identified. The species-richest animal groups of the macrozoobenthos were water beetles (Coleoptera), two-winged animals (Diptera) and water snails (Gastropoda). 19% of the detected species are listed in the Red Lists of Germany or Brandenburg as endangered, critically endangered or threatened with extinction (RL 1, 2 and 3).

The distribution of the macrozoobenthos species in the core area depends on a number of factors, the most important of which are the hydrological water type, the morphological water structure and the physical and chemical water quality. The typing of the water bodies carried out on the basis of these factors revealed the potential distribution of dominant species communities.

In the area of the Oder and the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße, five species communities have been differentiated that have different substrate requirements and different flow preferences. In terms of nature conservation, the species community of the backwaters of the recent floodplain that has been documented in the area of the Oder foothills, which is caused by the occurrence of the river feather gill snail (Valvata naticina) is marked.

Five species communities were also differentiated within the polder waters. In the core area, the species community of the oxbow lakes dominates, in which there are predominantly less specialized species. They have their main distribution center in still waters rich in aquatic plants with muddy soils. Highly specialized species are found in the polder waters within the silting sections of waters that have high water level fluctuations. Characteristic of the species community is the occurrence of the depressed feather gill snail (Valvata pulchella).

Another species group of the polder waters that is significant in terms of nature conservation is the fauna of the temporary and periodic waters. The species of Rossmaessler’s post squirrel, which are significant in terms of nature conservation (Gyraulus rossmaessleri) and lipped cuttlefish (Anisus spirorbis) as well as the back scarf (Lepidurus apus) could be detected in waters of this type.

The springs and source streams, for example in the Gellmersdorfer Forest, form an important habitat in the core area for the aquatic fauna. They are home to a fauna that is rare in Brandenburg and is characterized by flow-loving species that are adapted to low water temperatures. The evidence of the caddis fly species is significant (Rhyacophila nubila) and the water beetle (Limnebius truncatellus) in this type of water.

The comparison with the other results already available for the study area shows that all previously reported species could still be detected.

back to top![]()

Mollusks

In the Brandenburg part of the lower Oder valley, 140 species of molluscs have been identified, including 73 species of land gastropods, 46 species of water snails and 21 species of mussels. The lower Oder valley is home to 89.5% of the mollusc species documented in the state of Brandenburg.

Mud snail

![]()

Insects

Weaving spiders

20,624 spiders were caught with the help of floor traps, stripe-netting and tapping screens, of which 19,313 animals could be identified by the species. A total of 301 species have been identified in the last few years.

53 species (17.6%) are on the red list of endangered spiders in Germany. In terms of nature conservation, the occurrence of the water spider is to be assessed as particularly high, since it is listed as threatened with extinction in the Federal Species Protection Ordinance. Eight species are listed in the hazard categories RL 1 and RL 2 of the Red List of Germany.

The evaluation of the arachnological data proves the extraordinary wealth of the spider fauna, especially the high proportion of endangered and key species. This shows that the dry polder, which is used intensively for agricultural purposes, is significantly poorer than the wet polder, both in terms of the number of Red List species and in terms of the number of individuals.

Dry grassland and dry warm forests on the valley slopes, reed beds, wet and humid meadows, floodplain and high forests as well as still waters and slowly flowing waters with pronounced aquatic plant populations are the habitat types suitable for spiders.

Zebra spider

Further reading

Locusts

The locusts have only recently become popular bioindicators for grassland ecosystems. So it is not surprising that so far there is hardly any local work on grasshopper faunistics.

A total of 33 species of locusts were detected in the project area, 29 of them in the core area. As part of the investigations for the maintenance and development plan, 25 species of locusts were recorded in 1995, including nine species of long-probe (Ensifera) and 16 species of short-probe (Caelifera) grasshoppers.

Six species are classified as endangered on Germany’s Red List, predominantly drought-loving species. In earlier investigations, the only evidence of the steppe snake was found (Platycelis montana) which is classified as missing in the Brandenburg Red List (RL 0). In addition, five more nationwide endangered (RL 3) or endangered species (RL 2) identified.

Most endangered grasshopper species are xerophilic or mesophilic and, as the most severe species, are restricted to dry grasslands. In the valley lowlands, large sedge bogs with loose vegetation such as in the Fiddichow Polder and areas with diverse interlinking of different structure types and moisture levels such as Crieort (Polder A) have favorable conditions for a meadow-typical grasshopper settlement.

Field grasshopper

Further reading

Dragonflies

A total of 48 dragonfly species were detected, of which 37 species were also documented in 1995 as part of the investigations carried out for the care and development plan through imaginal observations, exuvia and larvae finds. Thirteen species are on the Brandenburg Red List, which proves the paramount importance of the study area for the dragonfly fauna.

The odonatological importance of the lower Oder valley is not only based on the 48 proven dragonfly species, but also on the vital reproductive population of the Asian wedge damsel (Gomphus flavipes), the occurrence of the common wedge maiden (Gomphus vulgatissimus) and the green maiden (Aeshna viridis). The green maid of the mosaic (Aeshna viridis) the Asiatic maidenhead lays its eggs only on the crab claws (Gomphus flavipes) needs the sandy banks of the Oder for their larval development. Both species are listed as critically endangered in the Federal Species Protection Ordinance.

In the course of their development from egg to imago, the demands of dragonflies on their habitats change considerably. In particular, the water morphology, flow speed, durability of the water flow and vegetation characteristics are decisive. Important habitats in the study area are springy and partially shaded streams, plant-rich oxbow lakes and temporary waters with changing water levels and sandy river banks.

Banded demoiselle

Ground beetle

More than 13,000 carabids were caught in 82 soil traps as part of the waterfront strip program. From this, a total of 204 ground beetle species were identified for the core area in 1994 and 1995. Of these, 49 species are on the Red Lists of Germany and Brandenburg, including Ophonus puncticollis and Platynus krynickei as threatened with extinction (RL 1), 15 more as severely endangered species (RL 2). Nine species are specially protected by the Federal Species Protection Ordinance.

The most important environmental factors for colonization by ground beetles must first be sufficient soil moisture and woody stocks. In the core area, most ground beetles can be found on the one hand on dry grassland locations, on the other hand on moist to wet open land biotopes, for example large sedge and reed bogs.

Musk buck

Wild bees

So far, 138 species of wild bees have been identified in the project area, 118 of which were recorded as part of the work on the maintenance and development plan. A further 20 species of wild bees were found outside the sample areas of Flügel and Franke. Species that are particularly noteworthy in terms of fauna are the masked bees (Hylaeus cardioscapus) and the furrow bee (Lasioglossum pallens). The furrow bee was detected for the first time in Brandenburg, the mask bee even for the first time in Germany.

The high proportion of endangered species is significant in terms of nature conservation. 38, i.e. 27.5% of the species found are threatened in the Federal Republic of Germany. Over half of the detected wild bee species are tied to a special nesting or feeding habitat.

The distribution of wild bees depends on suitable nesting sites, pollen plants and materials for building brood cells. Accordingly, the warm and dry habitats in the core area are of particular importance. These include dry lawns, dry pits, ruderal areas, rinsing areas and dike sections with sparse vegetation. Other habitats that are particularly important for specialized species are softwood meadows and willow bushes as well as wet and wet meadows.

Bee on crocus

Butterflies

Of the 532 species of butterflies and moths found in the core area, 120 are listed in the Brandenburg Red List. Of these, six species are classified as critically endangered (RL 1) and 29 as critically endangered (RL 2). According to the Federal Species Protection Ordinance, 89 of the detected species are specially protected and two are threatened with extinction. As a “kind of common interest” is the blue guy (Lycaena dispar) listed in Annex II of the Habitats Directive. The species is tied to extensively used grassland and was detected outside of the sample areas on the Jungfernberg and Silberberg (cf. Richter 1979, 1982a, 1982b, 2017).

With around 200 recorded species, the Gellmersdorfer Forest and the ecologically richly structured Densen Mountains, which are predominantly covered with dry grass, have proven to be particularly rich in species. The polders, on the other hand, are home to only a few species. The only interesting butterfly areas here are large sedge bogs, reed beds, floating leaf communities, alder quarries and deciduous forests. The grasslands are of very little importance for the butterfly fauna because they are still used intensively. Typical floodplain species tied to willows and poplars are rare or completely absent, as the pupae overwintering in the ground do not survive the regular, large-scale flooding in the wet polders. But the more lepidopteran fauna of the dry grassland locations also suffers from islanding and species decline, so that butterflies that are loyal to the location are particularly dependent on the development of a biotope network system.

Imperial coat

![]()

Fishes

Of the 45 species of fish found, 16 are only documented by individual finds, some of them decades ago. 27 species are recorded on the Red Lists of Brandenburg and Germany.

In the last few years the Wild Fish Section in Schwedt has repeatedly carried out stock-taking and identified 38 species by 1991 (Beschnidt 1991, 1995). In terms of nature conservation, the abundant occurrences of the nationally threatened bitterling species are particularly significant (Rhodeus sericeus amarus), Loach (Cobitis taenia), Mud whip (Misgurnus fossilis) and Zope (Abramis ballerus) as well as the regular individual finds of sea trout (Salmo trutta) and the river lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis).

As part of the investigations for the maintenance and development plan, 25,000 fish were caught on 63 representative sample stretches. Very different methods were used, from electric fishing to pulling, sinking and gillnet fishing to fishing traps and hand nets. A total of 28 species of fish, including 18 species on the Brandenburg Red List, were identified in this way.

The roach (Rutilus rutilus) with 15,000 animals, more than 1,000 specimens were from the perch (Perca fluviatilis) and from the bream (Blicca bjoerkna) caught while Aland (Leuciscus idus), Pike (Esox Lucius), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophtalmus) and bleak (Alburnus alburnus) with over 500 copies each. Bitterling (Rhodeus sericeus amarus), Common bream (Abramis brama), Gudgeon (Gobio gobio), Ruff (Gymnocephalus cernua), Burbot (Lota lota), Tench (Tinca tinca), Loach (Cobitis taenia) and Zope (Abramis ballerus) could still be proven with more than 100 copies.

Common bream

The occurrence and distribution of fish species are determined by their species-specific connection to main habitat types and the requirements for spawning grounds. The populations of plant-spawning still water dwellers in the study area are optimally developed. Marin-limnic species occur, apart from eel (Anguilla anguilla) and smelt (Osmerus eperlanus), only as single copies. Flow-loving gravel spawners do not find any spawning grounds in the area and, with a few exceptions, only occur as individual specimens that have migrated. For the reproduction of the pike (Esox Lucius) the flooding of the spawning meadows in spring is particularly important.

The two main waters of the Oder and Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße, the lake-like and elongated polder waters, the ditches in the south of the core area, the Oder foreland waters and the lower reaches of the Salveybach are important for fish ecology. From a nature conservation point of view, the evidence of currently still safe, high-individual populations of bitterling in the study area is significant (Rhodeus sericeus amarus), Burbot (Lota lota), Mud whip (Misgurnus fossilis), Loach (Cobitis taenia) and Zope (Abramis ballerus). These species, which are threatened nationwide and in the state of Brandenburg, have a special indicator function for the maintenance and development plan because of their high demands on their habitat. Some of them are described below in alphabetical order:

Eel (Anguilla anguilla): 64 specimens of the eel were detected on 27 test stretches. As a habitat, he prefers running and still waters that are connected to the sea. Stocking measures also lead to it getting into isolated waters. It colonizes bodies of water from the brackish water zone up to a height of 1,000 m. His way of life is soil-oriented. During the day it hides between roots, water plants or hollows. With the onset of dusk it becomes active and goes in search of food. Eels are very adaptable to water pollution and hydraulic engineering measures. To spawn, the animals migrate 5,000 to 7,000 kilometers into the western Atlantic from July to October. They release the eggs at a great depth. The parents probably die afterwards. The elongated larvae, about 6 millimeters in size, develop from the eggs and drift with the Gulf Stream to Europe within three years. In doing so, they change their appearance, developing into willow leaf-like, transparent Leptocephalus larvae over the course of the months. When they reach the coast, they transform into glass eels around 65 millimeters in size. These climb up the rivers as so-called Steigaale even over larger obstacles, whereby many of them perish. The eel is classified as potentially endangered in the Brandenburg Red List (RL 4) and as endangered in the Federal Red List (RL 3). Although a denser eel population could be expected in the study area due to the water structure and the water quality, due to the spatially wide life cycle an assessment of the risk situation for a relatively limited habitat is not possible.

River eel

Aland (Leuciscus idus): The Aland was proven in 724 copies on 44 test stretches. It prefers medium to large rivers and lakes as a habitat and lives sociable, often in schools. Very old animals sometimes appear as solitary animals. From March to May the mature animals migrate upstream, each female lays 40,000 to 100,000 eggs. They stick to plants and stones. The diet consists of worms, small crustaceans and insect larvae. In the Red Lists of Brandenburg and Germany, the Aland is listed as endangered (RL 3). The stock situation in the study area is favorable and any risk can currently be ruled out.

Bitterling (Rhodeus sericeus amarus): 331 specimens of the bitterling were caught on 13 test stretches. It prefers plant-rich bank regions of stagnant and slowly flowing waters with sandy to muddy bottoms. It is a sociable species of small fish that needs mussels to reproduce. In the spawning season between April and June, the male leads a female to a selected mussel that is defended against competing pairs. By means of the laying tube, which the female inserts into the outflow opening of the mussel, a few eggs are placed between the mussel gill lamellae during the repeatedly repeated spawning process. Then the male releases his semen via the inlet opening of the mussel, which is then washed to the eggs by the water flow. Females can lay 40 to 100 eggs per spawning period. The development of the embryos takes place in the gill space of the mussel. After two to three weeks, the fish larvae hatch and then leave the mussel a little later as buoyant fry. The larvae then around 10 mm in size initially feed on plankton. When the animals have grown up, they eat small invertebrates and algae. The bitterling was also only detected in the polder waters, both in the dry polder and in the wet polder. The Brandenburg Red List lists it as critically endangered (RL 1), the German Red List as an endangered species (RL 2). It is not endangered in the study area itself.

Perch (Perca fluviatilis): 3,925 specimens of the perch were caught on 60 test stretches. As a habitat, it populates a wide range of flowing and still waters. It occurs from brackish water areas to mountain waters at an altitude of 1,000 m. The biology of this species is characterized by its great adaptability to different environmental conditions. In their youth the perch are swarm-forming, in old age they appear as solitary animals. To hunt, the perch often form hunting parties and drive other fish into groups in order to then advance on the prey. Spawning time is between March and April, the eggs are laid in the form of up to 1 m long gelatinous bands in the bank area on plants, roots and stones. Young perch eat small invertebrates, older perch mostly fish.

Perch

Pike (Esox Lucius): 597 specimens of the pike were found on 51 test stretches. As a habitat, it prefers slowly flowing rivers with still water zones, oxbow lakes and oxbow lakes. He loves clear, herbaceous shallow lakes with a gravel bottom. It can colonize bodies of water from brackish water up to an altitude of 1,500 m. The pike is a predatory fish that is true to its location and that forms its territory and that does not allow any other species to enter its territory. As a loner, it lurks motionless in hiding for prey. Due to its coloring and behavior, it is so well camouflaged that fish and other prey swim close to it without noticing it. Pike spawn between February and May in weed-rich shallow water zones, flooded riverbank meadows and in ditches. The sticky eggs are laid on blades of grass and water plants. Depending on the water temperature, the larvae hatch after 10 to 30 days. The brood feeds on small crustaceans, later on insect larvae and invertebrates. For larger pike, fish are the main food. In addition, crabs, frogs, water birds and small mammals are also eaten. In the Stromoder and in the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße the pike was found comparatively rarely, but it was often found in the Oder foreland waters of the dry polder. While it is rare in the dry polder itself, it is more common in the Criewen polder, even more numerous in the Schwedt polder and most often in the Fiddichow polder. Both juveniles and adults were detected everywhere. The latter preferred the large lake-like bodies of water, while the juveniles stayed mainly in the heavily weed, elongated, rivers-like ditches. In the Red Lists of Brandenburg and Germany, the pike is listed as endangered (RL 3).

Pike

Roach (Rutilus rutilus): A total of 15,331 individuals from the roach were caught on 60 test stretches. This makes it by far the most common fish in the lower Oder valley. Their habitat is standing and slowly flowing water. It can also penetrate the brackish water. It is considered to be an adaptable schooling fish that is relatively insensitive to water pollution. It can be found regularly in grassy bank areas and in open water. If there is no predatory fish population, it tends to develop in masses and then to fodder. The spawning season is between May and April, the spawning schools prefer to lay their eggs in shallow water on plants, roots and stones. Depending on their size, the females lay 50,000 to 100,000 eggs. The larvae that hatch after four to ten days first use up their yolk sac and later eat plankton and small invertebrates.

Burbot (Lota lota): The burbot was detected with 341 specimens on 27 test stretches. It colonizes around half of all investigated water bodies. As a habitat, it prefers lakes and rivers, especially cool, clear and oxygen-rich water. It occurs from brackish water up to an altitude of 1,200 m. The burbot is a nocturnal bottom fish. It spawns between November and March after some very pronounced spawning migrations. The eggs contain an oil ball and are planktonic. The development time is between 45 and 75 days, depending on the water temperature. The burbot is classified as endangered (RL 2) in the Brandenburg Red List as well as in the federal government. Strong stock slumps characterize the risk situation nationwide. In many areas the stocks are almost extinct. As with the Zope, hydraulic engineering measures and water pollution in particular are responsible for the decline in the population. Only a few bodies of water still have intact populations. The burbot is a non-endangered species in the study area. The age structure suggests suitable reproductive conditions. The water quality does not seem to have a negative impact on the population either.

Burbot

Mud whip (Misgurnus fossilis): The mud whip was detected in 25 specimens on 5 test stretches. As a habitat, it prefers plant-rich still waters, ponds, ponds as well as riparian zones, oxbow lakes and floodplains of rivers. It can also be found in slowly flowing meadow ditches and streams. The mud whip is a nocturnal, stationary bottom fish. During the day it hides close to the ground between aquatic plants, roots or in the mud. Since it can cover up to two thirds of its oxygen needs with the help of its skin breathing, it is adapted to these living conditions. The mud whip can bridge a major lack of oxygen in the water by swallowing air in the intestine, which is rich in blood vessels. The used air is expelled through the anus. The animals survive a dry fall of the residential water for several months, buried up to 75 cm deep in the ground. During the spawning season between April and June, the sticky, brownish eggs (up to 150,000 pieces) are laid on aquatic plants. The larvae have thread-like outer gills. The food is made up of small invertebrates and decaying parts of plants as well as carrion. The Schlammpeitzger also only inhabits the polder waters, especially smaller, heavily weed and muddy ditches.

Wolffish (Cobitis taenia): The wolffish was detected on 29 test stretches with 163 specimens. As a habitat, it prefers clear streams, rivers and the shoreline of sandy lakes. He is a stationary bottom fish. The animals burrow up to their heads during the day to search the ground for food at dusk and at night. With the help of the whiskers they find their food, which consists of small animals such as rotifers, hippopotamuses, water fleas and mussel crabs, but also of dead organic components. The spawning season is between April and June. The sticky eggs are laid on stones, roots and aquatic plants. In the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße, the wolffish was rarely found, in the Oder sporadically. The main focus of its distribution is in the polder waters, in the dry polders as well as in the wet polders. The wolffish is most common in the Schwedter Polder, less often in the Criewener Polder and only sporadically in the Fiddichow Polder. There it populates mainly smaller, elongated, flowing water-like types of water. Both young and adult animals were detected in all test stretches in the polder area, so that normal reproduction in the examination area can be assumed. The Red List of Brandenburg and Germany classifies the wolffish as critically endangered (RL 2). This risk does not currently apply to the study area.

Steinbeisser

Bleak (Alburnus alburnus): 624 individuals of the bleak were caught on 31 test stretches. Their preferred habitat are stagnant and slowly flowing waters. It is a surface-oriented schooling fish that can be found regularly even in the middle of the water. Like most other species, it has its main distribution near the shore. Mass occurrences are typical of bleak. During the spawning season between April and June, the fish seek out shallow banks, where they lay around 1,000 to 1,500 eggs on stones, roots and plants. The food is made up of small invertebrates, approaching insects and plankton. The bleak is listed in the Brandenburg Red List as an endangered species (RL 3), at the federal level it is not endangered.

Zope (Abramis ballerus): A total of 470 specimens of the Zope were caught on two test stretches exclusively with traction nets. It is considered to be an open water species of the slowly flowing lowland waters, river lakes and rarely also of the brackish water zones. During the spawning season between April and May, the zopes migrate upriver to spawn in groups between shallow, flowed-through aquatic plants or flooded land plants. 4,000 to 25,000 sticky eggs adhering to the plants are given off per female. The food in the river consists mainly of plankton, crustaceans and insect larvae. In winter, when there is little plankton supply, the zope retreats into deep areas of the water. It is on the Brandenburg Red List as critically endangered (RL 2) and on the Red List of the Federal Republic of Germany as endangered (RL 3). The declining population development can be attributed to the reduction in suitable spawning waters. It currently appears to be safe in the study area.

Of course, it is difficult to categorize the water locations according to their suitability for the fish fauna. Distinguishing the Oder, the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthal waterway and the polder waters, one can nevertheless make the following generalizations:

In the Oder the biodiversity was below average on the bank sections fortified with protective stones without reeds and woody vegetation. The roach usually dominates here, while demanding species such as the wolffish do not occur.

On the Oder, the stretches of water between the groyne fields and in the sections with heavily overgrown riparian zones originally built with rock fillings are of average importance. They all have relatively natural bank structures. Trees or dense reeds are characteristic here, the dominance of the roach is less developed. Due to the more frequent occurrence of other species, the species structure is generally more balanced. The wolffish and burbot regularly appear as species with special indicator significance.

From a fish-ecological point of view, on the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße, only below-average test stretches can be detected in the narrow, channel-like sections fortified with protective stones. Average significant test stretches are located in areas where the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler waterway runs through old branches of the Oder and therefore natural profiles and bank shapes predominate. With the polder waters of different types and sizes, the heavily silted and shallow lake areas with a low density of aquatic plants can be described as below average. Roach and perch dominate here, while more demanding species such as bitterling and wolffish are absent. The average significant areas are mostly located on larger lakes, which have more pronounced depths in the shallow water zones. The shallow water zones are mostly made up of aquatic plants, the banks often used as pasture right up to the water. Lakes with a typical zoning of aquatic plants and with at least partially tree-lined banks are of above-average importance. Shallow water zones and depth areas are in a balanced relationship. The occurrence of wolffish and bitterling as well as of the still water species rudd and tench is characteristic of the test stretches.

Further reading

![]()

Amphibians

While no specific investigations of the amphibian fauna were carried out in the Oderaue itself until the mid-1990s, the Schwedt biology teacher, Jörg Wilke, began regularly with his students to map the small bodies of water (Feldsölle) of the hill country in the east of Bavaria as early as the mid-1980s.

During the investigations for the maintenance and development plan, a total of ten amphibian species were identified by interrogating the voices and searching for suitable bodies of water — each test area was visited seven to nine times in the spring, including two at night. eleven species are currently found in the national park area (HAFERLAND 2012). All are under the protection of the Federal Species Protection Ordinance. Nine species are on the Red Lists of Germany and Brandenburg, five in the Habitats Directive. The amphibian species are named in decreasing frequency: pond frog (Rana kl. esculenta), Sea frog (Rana ridibunda), Common toad (Bufo bufo), Moor Frog (Rana arvalis), Common frog (Rana temporaria), Common garlic toad (Pelobates fuscus), Fire-bellied toad (Bombina bombina), Pond newt (Triturus vulgaris) and Tree frog (Hyla arborea). The green toad (Bufo viridis) was only found outside of the sample areas at the time, at present this species is occasionally found in the southern part of the national park (HAFERLAND 2012). Half of the amphibian species native to the Federal Republic of Germany are found in the project area, 14 of them live in Brandenburg. The crested newt (Triturus cristatus) and the little water frog (Rana lessonae), which Wilke (1995) was able to detect in the Schwedt / Angermünde area, were not found in the core area.

The two green frogs were found in all study areas, and the common toad was also quite widespread. Fire-bellied toad, tree frog, common garlic toad and moor frog avoid the low-lying parts of the wet polders. They have their distribution focus in the area of the Lunow-Stolper Polder (dry polder), but increasingly colonize the flood polders and expand their area of occurrence, like the tree frog, to the north. Common toads and common frogs prefer to settle in the meadows and wet forests at the foot of the valley slopes north and south of Stolpe.

Tree frog

A typical, species-rich amphibian body of water has clean water, pronounced shallow water zones with submerged vegetation and a structure-rich environment. Amphibians overwinter in frost-protected places, most of them burrow on land in crevices and hollows. The cold-blooded animals survive the cold season by falling into cold rigidity.

Short-term floods and increases in the groundwater level are tolerated by all species during this period. Long-term floods drown many of the amphibians that normally hibernate in the countryside. The situation is different with the sea frog and the pond frog, which overwinter in the water. Their populations are not permanently affected by the winter floods.

Because of the species-rich amphibian population, the Lunow-Stolper Polder, the Oder foreland along this polder and the Crieort area are particularly significant. The surveys show how important the dry polder is, especially for amphibians.

Further reading

![]()

Reptiles

For reptiles, too, there were no systematic investigations in the lower Oder valley until the early 1990s, only random observations by volunteer conservationists and the nature watch. As part of the investigations for the care and development plan, a total of four types of reptiles could be identified through targeted searches for existing hiding places and the construction of artificial hiding places: The sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) was particularly common on the dry slopes, but was also found occasionally in the polder area. The forest lizard (Lacerta vivipara) could only be found on two areas on the edge of wet meadows, the slow worm (Anguis fragilis) can only be observed on the dry grassland and hillside forest locations, while the grass snake (Natrix natrix) occurs almost everywhere in the polder area.

Lizard

There is also an earlier evidence of the smooth snake from the lower Oder valley (Coronella austriaca) (1989), three specimens of the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis) have been discovered in the Criewener polder, i.e. a total of six reptile species since 1989 that are threatened according to the Red List of the State of Brandenburg and are protected by the Federal Species Protection Ordinance.

The large population of sand lizards and grass snakes can be classified as nationally important. Otherwise, wet polders in particular are not suitable reptile habitats, not least because of the regular flooding that only the swimming grass snake can cope with. But it also needs flood-proof winter quarters.

From the point of view of reptile protection, the dry grassland and flushing sand areas close to the water are important as potential egg-laying places for the pond turtle, while the valley flanks with their exposed dry grassland and dry forests are important habitats for the sand lizard.

Grass snake

Further reading

![]()

Birds

- Birds by habitat:

- Water bird census

As part of the preparation of the maintenance and development plan, a comprehensive map of the key species was created for the breeding birds. This list of all breeding birds observed in the area since 1961 included 161 species, 141 of which brood regularly. This list of species has been thoroughly revised in recent years (HAFERLAND 2010, 2012) and currently includes 293 species that have been identified within the boundaries of the national park. 63 species (including 51 as breeding birds) are on Brandenburg’s Red List, 46 on Germany’s Red List, 18 species are threatened with extinction according to the Federal Species Protection Ordinance, 51 are listed as particularly worthy of protection in the EU Birds Directive (see Table 2). At least 14 species have over 10% of their Brandenburg breeding population in the lower Oder Valley, i.e. 0.3% of the land area, with the Black Tern (Chlidonias niger) it is even 30 %, in the case of the Corn Crake 17% of the globally endangered German population.

The 147 species currently breeding regularly in the area comprise 85% of Brandenburg’s breeding bird species. Of these, 17 species are in the endangerment categories (RL 1) and (RL 2) the Red List of Germany.

On the sample plots at that time, settlement densities were found for many of the more common songbirds, which are among the highest in Central European comparison. For 14 migratory bird species, the one percent criterion of the Ramsar Convention is exceeded regularly or in individual years. It states that at least 1% of a large population regularly rest in an area. The project area is also of nationwide importance for ruff due to the high number of individuals during the migration period (Philomachus pugnax), Common Snipe (Gallinago gallinago), Wood sandpiper (Tringa ochropus), Miniature snipe (Lymnocryptes minimus) and water pipit (Anthus spinoletta). The Corn Crake (Crex crex) has one of its largest deposits in Germany in the lower Oder valley. 30 percent of the German black tern breeding population (Chlidonias niger) are located in the lower Oder valley. The reed warbler (Acrocephalus paludico) only occurs in Germany in the lower Oder valley with males singing irregularly at present.

Over ten percent of the Brandenburg breeding population is concentrated in the lower Oder valley for a further eleven species. Of these, sprouts reach here (Luscinia luscinia), Schlagschwirl (Locustella fluviatilis) and carmine pennants (Carpodacus erythrinus) their current western limit of distribution. The Goosander (Mergus merganser) has its largest occurrence in the lower Oder valley and expands it every year. The cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) The establishment of a larger breeding colony at the Wrechsee near Schwedt in the lower Oder valley was not successful until 1994, after several breeding attempts in the previous years had been thwarted by active deterrence.

Wet polders with backwaters, dry grasslands with bushes and near-natural forest stands are of particular ornithological importance. Since especially many bird lovers visit the lower Oder valley, it seems to be useful to go into some particularly interesting species, sorted by habitat, in more detail. The beginning is made by the biotopes of the Oder floodplain.

A current annotated list of species can be found at HAFERLAND, H.-J. (2010): List of species of birds in the Lower Odertal National Park, In: Vössing, A. (Ed.) Lower Odertal National Park Yearbook (7), 115–130, Lower Odertal National Park Foundation, Criewen Castle, Schwedt / O. This list was supplemented in 2012 (HAFERLAND 2012).

Wet meadows

The lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) prefers not too high and not too dense vegetation on cultivated meadows and pastures with waterlogging points for its settlement. Accordingly, the lapwing occurs primarily in the wet polders, where it concentrates on the wettest areas, in particular on the depressions in front of the paper mill in Fiddichower and in the Schwedter polder. By quickly pumping out the water, part of the lapwing territory is left again later. In the dry polder, in addition to the humid Odor foreland, waterlogging areas are populated in the arable land, but hardly the cultivated grassland. In the Friedrichsthaler Polder there is a concentration on moist, but still used grassland.

Lapwing

The Common snipe (Gallinago gallinago) prefers a rather high vegetation, gladly also uncultivated areas, for example very moist, waterlogged meadows. It is well represented in the Fiddichower and Friedrichsthaler polder, in the dry polder it concentrates on the few wet areas. For the common snipe, too, a possible breeding success is often negated by the early pumping out of the wet polders (KUBE 1988A and B, DITTBERNER 2014).

Common snipe

The habitat The Great curlew (Numenius arquata) are spacious, moist, as short-grassed as possible and not too dense meadows and pastures with waterlogging points and open water. Of the meadow climates, the curlew is most likely to tolerate somewhat more intensive management. The few breeding pairs in the lower Oder valley are limited to the Friedrichsthaler polder south of Gartz (Oder).

Great curlew

Similar to the black godwit and lapwing, the colonizes Redshank (Tringa totanus) moist, not too tall and dense grassland. Larger waterlogging areas with muddy banks and clear vegetation are important. The redshank occurs mainly in the wet polders, but some pairs also breed in the Friedrichsthaler polder and in the Odervorland Lunow-Stolzenhagen.

Redshank

The Corn Crake (Crex crex) colonizes grassland with a vegetation height of 30 to 50 cm and with near-ground, dense, but still penetrable vegetation on moist, but not flooded ground. After his arrival (at the end of April) at the beginning of May, it initially occupied relatively tall water swathes, reed grass meadows and sedge meadows, while increased immigration to foxtail meadows occurs in the course of spring. Both humid depressions and elevated and somewhat drier areas in the grassland as well as individual bushes that it uses as a singing area, as well as high shrub fringes that it uses as moulting areas after the breeding season are favorable for the corncrake. The lower Oder valley is one of the most important breeding areas of the corncrake in Germany. Most birds breed in the wet polder. The Friedrichsthaler Polder has been increasingly populated for some years now, in the dry polder calling animals are found in a few moist places and, above all, repeatedly in the Oder foothills. Above all, the corncrake can be found on the Lange Rehne, on the Heuzug and in the Schwedt polder.

Corn Crake

The last breeding areas The Sedge Warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola) are limited to polder 5/6, where extensive measures have been carried out in recent years as part of an E + E project to preserve and restore habitats of the species. This globally threatened bird species populates grassland areas with moist to wet ground and sedge stocks. The sedges, especially Carex gracilis, can form large areas or be limited to smaller island-like occurrences in cane grass meadows. Regular singing places have even been established in pure, high-growth reed grass meadows without sedges.

Sedge Warbler

Waters

The Red-necked grebe (Podiceps grisegena) does not love deep, sunny waters with dense submerged vegetation and floating leaf plants, especially smaller bodies of water, such as field collars, oxbow lakes and flood plains. As a breeding bird, the red-necked grebe is restricted to the wet polders in the lower Oder valley. Most attempts to settle in polder A / B on flooded meadows fail because the wet polder areas are pumped out.

Red-necked grebe

Of theKingfisher (Alcedo atthis) loves waters rich in small fish with suitable perch. Breeding sites are found in the edges of rivers and ditches, at excavation sites or in the root plates of fallen trees. In the lower Oder valley, the kingfisher is distributed fairly evenly over the entire area. Breeding sites are known both on oxbow lakes in the polder and in the hillside forests.

Kingfisher

The Black Tern (Chlidonias niger) As a colony breeder, specializes in the colonization of standing waters and oxbow lakes with pronounced floating leaf vegetation, in the past especially crayfish claws, today mostly sea or pond roses (cf. Krummholz and Krätke 1982) or in artificial nesting aids. It also breeds on grass or bent reed bulbs or small patches of mud on the bank. If extensive and permanently flooded meadows are available, black terns use protruding grass bulbs from them as breeding grounds. This was registered in the lower Oder Valley, for example, in 1994 during the long-term flooding (Grimm 1995). However, there was no breeding success due to the pumping out of the wet polder. In the lower Oder valley, the black tern breed mainly in smaller colonies on many oxbow sections, for example in the Criewener or the Schwedt polder. These smaller colonies are extremely sensitive to disturbances. The stock is subject to strong fluctuations every year, which can be traced back to various causes. In 2017, for example, Black Terns brooded in seven places with a total of 215 pairs, with around 140 sweaters hatching, of which at least 72 fledged (Krummholz, unpublished).

Black Tern

Reeds

That Bluethroat (Luscinia svecica) finds good living conditions in the lower Oder valley. As a breeding ground, it prefers silting areas with reed beds and willow bushes. Places with sparse vegetation for foraging on the ground, free access to the water, but also areas with dense vegetation rich in cover are important. These conditions are met above all by young succession stages, as they arise again and again, in particular due to the dynamic processes of a flowing water. In Brandenburg, the species is largely restricted to the floodplains and some larger lakes, while in other areas of Germany secondary biotopes and increasingly even ditches in the agricultural landscape are often populated. In the lower Oder valley the Bluethroats breed mainly in the Fiddichower polder near Friedrichsthal, but also occasionally in the dry polder.

White-starred bluethroat

The Feldschwirl (Locustella naevia) breeds in grass and tall herbaceous meadows in the open and semi-open landscape. The herb layer must be dense, but penetrable at the bottom and have protruding stalks as a singing point. In the lower Oder valley, it breeds in the polders on the edge of the reed beds as well as on paths and ditches and in the moist grassland areas, preferring fallow meadows and pastures. It also breeds on the edges of the softwood floodplains, for example on the northern edge of the Schwedter Querfahrt and northeast of Crieort, in the valley edge areas also in open spring bogs and in tall herbaceous areas on dry grasslands. The species benefits from the creation of wilderness zones and extensive grassland use.

The Rohrschwirl (Locustella luscinioides) usually nests in larger reeds. The landside areas with a dense soil layer of sedges and herbs as well as old reeds are preferred to be populated. In the lower Oder valley, such habitats are often found on the banks of the oxbow lakes and in the reed strips in the Oder foothills. In recent years, reed-free, fallow grasslands have increasingly been populated, provided they stand on moist ground and contain other herbs and perennials in addition to sedges and reed grass. In the Nasspolder, the Rohrschwirl breeds mainly in Polder 10, in the Wrechsee area, but also on the reeds on the banks of the oxbow lake, also in the northeast tip of the Trockenpolders, on the Stolper Strom and near Friedrichsthal. The species has increased significantly in recent years.

Similar to the Rohrschwirl also colonizes Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus) reeds interspersed with a rich layer of sedges and herbs. In the Lower Oder Valley, the reed strips on the oxbow lakes are densely populated in many places, even if they are only a few meters wide. In the more humid areas, the reed warbler can also be found all over the grassland, provided that sedge stands or tall reed grass meadows predominate on the damp ground. This species also benefits from the decreasing cultivation intensity. The reed warbler inhabits the polder area in a similar distribution as the reed warbler. In the Friedrichsthaler Polder, too, the edges of the altar are densely populated, especially north of Friedrichsthal.

The occurrence The Throttle tube warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) limited to high, water-based reed stands without any noteworthy herbaceous layer. Although most of the occurrences are found in larger reed stands on oxbow lakes, for example on the Wrechsee or in the Oder foothills, remarkably small reed beds are occasionally populated, for example in some places in the dry polder. Other focal points are on the Welsebogen and on the banks of the West or south of Gartz and Staffelde.

Great Reed Warbler

The following biotopes can be found both in the Oder floodplain and in the hillside forests.

Woods

The Sprout (Luscinia luscinia) colonizes softwood meadows and smaller willow bushes on moist ground with a partially missing but partially well-developed herb layer. He avoids dense closed forests, usually also their edges, his territories are either in the semi-open landscape or in heavily loosened larger trees with clearings and free spaces. In the wet polders area, the sprout occurs almost everywhere in all suitable places, while it is somewhat rarer in the dry polders and in the Friedrichsthaler polder, in the peripheral areas only sparsely in semi-open wet areas.

The claims of nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos) resemble those of the sprout, but it also uses drier woody plants. The Lower Oder Valley lies on the northern edge of its closed distribution area. While the nightingale is hardly less common than the sprout south of the Lower Oder Valley, it is already clearly behind it in the dry polder. The ratio between the two bird species is 1: 5. The species is currently increasing in population.

Nightingale

The districts The Blow whirls (Locustella fluviatilis) are characterized by a multilayered vegetation structure. What is important is a well-developed, richly structured, dense but penetrable herb layer at the bottom. Perennial nettle stocks are often populated with bent stalks or lying twigs. There should also be a layer of bushes and trees. Many swirling areas are located in relatively closed higher stands of trees, many also in dense willow bushes, sometimes even in individual willow bushes in the open countryside. Larger closed forests are not populated or only sporadically on the edge. In the Lower Oder Valley, the Schlagschwirl preferably breeds in the wet polders, especially in the Fiddichower Polder and on the Schwedter Querfahrt. The species is rare in the dry polder. On the slopes of the Oder valley it occurs only on the edge of the closed forests.

The Tasmanian tit (Remiz pendulinus) breeds in well-structured, semi-open woody plants, mostly on the banks of oxbow lakes in tall trees, near reed or cattail surfaces, from nettles and hops, which it uses as nesting material. Despite the best habitat conditions, the pygmy tit has been declining significantly for years, so that it is currently only rarely found as a breeding bird.

Tasmanian tit

The Carmine (Carpodacus erythrinus) prefers the loose softwood meadow with taller trees, willow bushes and open reeds and shrubs and avoids larger closed tree populations. The carminer lives in the Lower Oder Valley near its limit of distribution. The highest density is reached in the area of the Westoder near Friedrichsthal, which is likely to be related to the proximity to suitable habitats in the Zwischenoderland. Other, smaller concentrations can be found on the Schwedter Querfahrt, on the Großer Zug and on the oxbow lakes in the dry polder near Stolpe. In the German part of the Lower Oder Valley, the carmine pickle was only observed from 1974 in the course of its western expansion, and its population continued to increase in the 1990s (Dittberner 1996). at present the population increase has stopped.

Carmine

The Sparrowhawk Warbler (Sylvia nisoria) colonizes multi-tiered woody plants in the open landscape, both in very humid and in very dry areas. It is important to have some tall trees, which should not be too close together, and a well-developed layer of bushes, for example thorn bushes, willows and upstream stands of tall shrubs. Sparrowhawk mosquitoes often seek the immediate vicinity of red-backed shrimp, probably to exploit their enemy and warning behavior. They have high populations in the remains of the softwood alluvial forest in the polder area, for example in the Fiddichower Polder near Friedrichsthal and on the north side of the Schwedter Querfahrt and on the Großer Zug. The sparrowhawk warbler is rarer in the dry polder, but can be seen on richly structured forest edges, on field trees and dry slopes.

The Red backs (Lanius collurio) prefers thorn bushes in the semi-open landscape. Favorable, if not necessary, are tall trees and, in the immediate vicinity, extensively cultivated, moist or dry grassland that he uses for foraging. The red-backed shrike can be found in the softwood meadows of the polder area as well as on suitable woody trees on the slopes of the Oder valley, especially on dry grassland locations.

Red backs

The Gray shrike (Lanius exubitor) breeds in the semi-open area with bushes and trees, which he can use as sitting waiting areas. It needs pastures and meadows with loose vegetation, but also occurs in a richly structured arable landscape. In the Lower Oder Valley, between five and eight territories are mapped annually, but breeding evidence is less successful because this shrike is often very secretive during the breeding season.

Deciduous & mixed deciduous forest

theTurtledove (Streptopelia turtur) settles forests and woodlands of the semi-open landscape. Most of their territories are in loosened pine forests, often in peripheral areas, sometimes also in closed deciduous forests. A good sun exposure of the forests is obviously crucial for this warmth-needing species. The turtle dove is one of those bird species that has shown dramatic populations for several years. Currently only individual records are available from the national park, but they do not give any indications of breeding occurrences.

Dove

While the Stock dove (Columba oenas) is dependent on old book stocks, preferably the Black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius) Pines and beeches and the Middle woodpecker (Dendrocopus medius) Oak forests with a high proportion of dead wood for the breeding business. The three species were mainly observed in the Peterberg, Densenberg and Gellmersdorfer Forst. Both the Green woodpecker (Picus viridis) as well as the Small woodpecker (Dendrocopus minor) are not common either in the polders or in the hillside forests, but they do occur in moist deciduous forest areas. The stock dove and woodpecker species benefit from the non-use of forests and the associated increase in standing dead wood.

Middle woodpecker

The Yellow mockers (Hippolais icterina) inhabits woody plants with a dense, well-developed layer of bushes and mostly loose, towering trees in both moist and dry surroundings, but not in closed forests. In the polder area it breeds in softwood meadows, on the slopes it breeds preferably in places where moist forests border an open meadow landscape and whose transition areas are well structured by bushes, for example on the southern edge of the Gellmersdorfer Forest.

The Oriole (Oriolus oriolus) and the Graycatcher (Muscicapa striata) nest in the polder area as well as in the hillside forests. Similar claims as the Miniature flycatcher (Ficedula parva) and the Pied flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) mark the Wood warbler (Phyleoscopus sibilatrix). They all prefer the beech forests and the oak-hornbeam forests on the slopes of the Oder Valley, not least because of their multi-level age structure with a sparsely developed or even largely absent layer of bushes and herbs. Its main area of distribution is in the Gellmersdorfer Forest.

Marsh tit (Parus palustris) and Willow tit (Parus montanus) inhabit the deciduous and mixed forests of the Lower Oder Valley. Their main areas of distribution complement each other: In the softwood floodplains of the polder area the willow tit predominates, in the hillside forests the marsh tit.

Titmouse

Winter and summer golden chickens (Regulus regulus, Regulus ignicapillus) are bound in their occurrence to spruce and Douglas fir, as well as the bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) and the Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra). Most of the breeding pairs were found in the Densen Mountains, in the Peter Mountains and in the Gellmersdorfer Forest.

Bullfinch / Bullfinch

The Black kite (Milvus migrans) and the more common Red kite (Milvus milvus) breed in the woods of the open landscape and near the forest edge. The red kites are particularly easy to spot over the dry polder.

Red Milan

The Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) is the most common bird of prey in the Lower Oder Valley. Just like thatHawk (Accipiter gentilis) and theBrown owl (Strix aluco) it breeds mainly in the richly structured deciduous and mixed forests on the slopes of the Oder Valley. The tawny owl hunts both in the hillside forest and in the polder areas, while the Common raven (Corvus corax) Concentrated on the hillside forests, but also increasingly populated the direct floodplain (e.g. polder 5/6).

Common buzzard

Xeric grasslands

The Turning neck (Jynx torquilla) inhabits patchy, ant-rich dry grasslands with adjoining bushes and thick, cave-rich trunks. In the Lower Oder Valley, it is mainly found on light forest slopes and on clear cuts in the Densen Mountains, also on dry slopes and occasionally, mostly near the dike, even in the polder area.

The Woodlark (Lullula arborea) colonizes dry grasslands, the edges of loose pine forests, heather areas, clearcuts and well-defined forest edges. It is important to have a loose herbaceous layer with a proportion of sandy areas free of vegetation of at least 10% as well as loose trees and bushes. The best way to meet the biotope requirements is on the edge of the valley sand terraces north of Friedrichsthal, which are loosely lined with pine trees. In addition, the woodlark lives in suitable forest edge areas and open spaces, for example in the Peterberg Mountains and on an alluvial sand area in the polder near Stützkow.

Crested lark

The Meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis) colonizes moist but not wet grassland, provided that the vegetation is not too high and not too dense. It breeds in high stocks in the dry polder and in the polder 5/6, the flood polders are hardly populated any more.

Meadow pipit

The Yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava) inhabits the open landscapes of the polder area, in the dry polder especially the Oder foothills. The species reaches its highest density in wet meadows (cf. Dittberner and Dittberner 1991).

Yellow wagtail

That Whinchat (Saxivola rubetra) breeds in tall herbaceous corridors within moist and dry grassland areas with protruding stalks, stakes or individual bushes as perches. It avoids the humid areas of the wet polder and is mainly found in the Friedrichsthaler polder and on the dry slopes.

The Gray bunting (Emberiza calandra) colonizes the agricultural landscape, it avoids wet and damp green areas and prefers dry grassland with patchy vegetation, as it is found in the lower Oder valley, especially on the dry slopes.

For particularly rare large birds, nest protection zones have been established in accordance with the Brandenburg Nature Conservation Act.

The Marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus) breeds in larger reed areas of the Oder floodplain with currently a total of nine breeding pairs. The breeding population has increased in recent years.

Marsh harrier

Of the Crane (Grus grus) breeds either in reed beds, in moist alder forests or in alluvial forests, whereby it needs stagnant water and open spaces for foraging in the immediate vicinity. It is currently found with 51 breeding pairs / territorial pairs both in the polder area and in the moist edge areas of the hillside forests (Haferland unpublished). In the area of the old district of Angermünde and the city of Schwedt, 70 to 75 cranes brooded in 1994, around 15% of the Brandenburg population. In the Lower Oder Valley is one of the large inland gathering and resting places for the crane, which has been visited for at least 80 years (Robien 1928; Haferland 1984). The actual sleeping place is in the Zwischenoderland, due to the dyke slitting in the polder 8, the flooded area is also used as a sleeping place. For two years now, several hundred cranes have been sleeping in waterlogged sedge meadows in Polder 5/6. The food areas are on the arable land, partly also on the meadows, especially in the area between Gartz, Tantow and Casekow (Haferland 1995). The cranes can be observed in spring and autumn in the evening hours from the dike directly south of Gartz, from the slopes of the Silberberg or from the Stettiner Berg near Mescherin.

Further information can also be found on the page The migration of birds.

Crane

The White-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) has five breeding sites in the core area, the nests of the other sea eagle nests that can be observed above the Lower Oder Valley are located in the extensive hillside forests east of the Oder. The observation of a white-tailed eagle is not that rare and is certainly one of the highlights of a trip to the Lower Oder Valley (cf. Dittberner and Dittberner 1986).

White-tailed eagle

Also the Lesser Spotted Eagle (Aquila pomarina) currently no longer nests in the area, but occasionally observations succeed, not only at migration time, in the Oder Valley. The is represented by a breeding pair Black stork (Ciconia nigra), which mainly uses the damp and waterlogged peripheral areas for foraging. The hillside forests offer optimal breeding grounds for all three species, especially because of their rich mosaic of different landscape elements. Keeping these undisturbed is an important task of nature conservation.

Lesser Spotted Eagle

Further observations and publications are available for the whooper swan by KRUMMHOLZ (1981), for the dwarf swan by DITTBERNER & DITTBERNER (1984), for the quail by HAFERLAND (1986), for oystercatchers, shelduck and little tern by DITTBERNER & DITTBERNER (1986), for the cormorant by KRUMMHOLZ (1988), for the double snipe by KUBE (1991) and for the barn owl by SCHMIDT (1995).

Water bird census

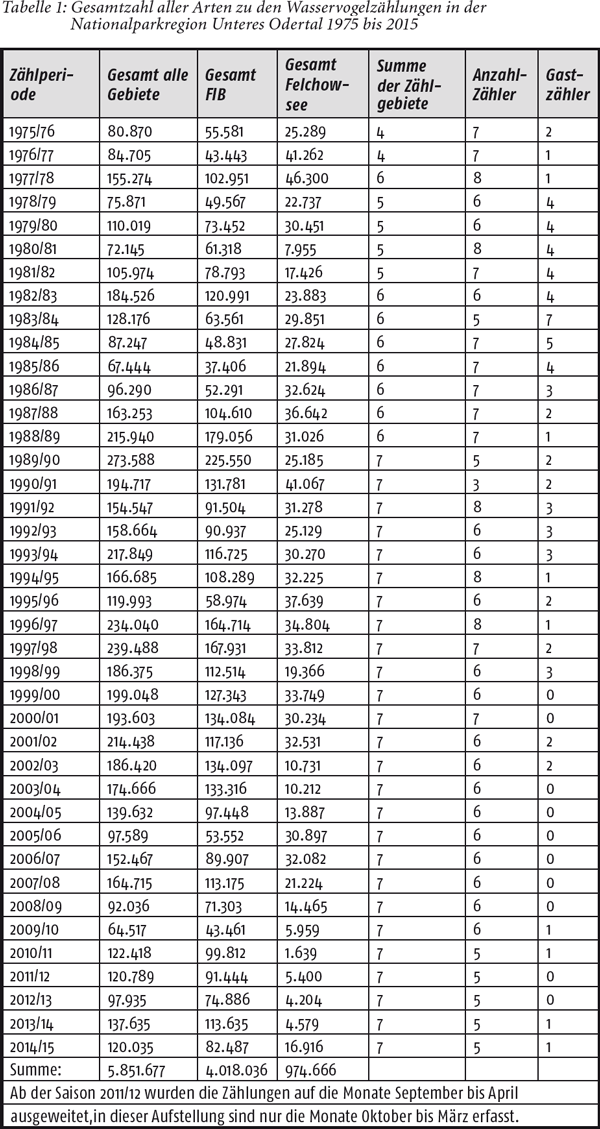

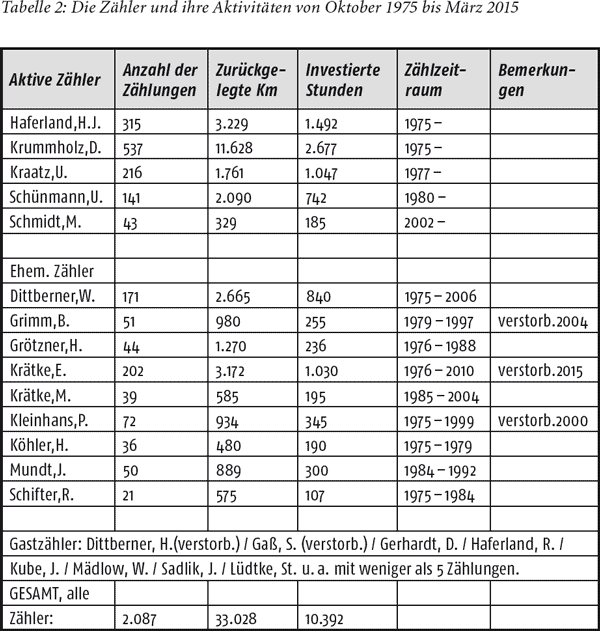

Since the mid-1960s, voluntary ornithologists have carried out counts of resting, migrating and wintering waterfowl, and since 1975, monthly surveys between October and March as part of the international waterfowl censuses. The organization of this census is in the hands of D. Krummholz. In the first ten years of this program, volunteers recorded a total of over 1 million water birds in the wet polders and on the Felchowsee alone.

The area is therefore of European importance as a breeding, resting and wintering place for rare or endangered bird species. For the area of the new federal states, the Lower Oder Valley is the most important spring resting area for waders and waterfowl inland and at the same time an important migratory axis in the system of European bird migration.

As part of the investigations for the maintenance and development plan, 158 water bird counts were carried out in eight areas of the Lower Oder Valley in the 1993/94 season. In addition to the polder area between Lunow and Gartz, the Felchowsee, Landiner Haussee and Stolper fish ponds were included in the investigations.

The wet polders are of greatest importance as a resting area in winter and spring. The following seven species fulfilled the 1 percent criterion of the Ramsar Convention almost every year from 1990 to 1994: Whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus), Bean Goose (Anser fabalis), White-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), Gadfly (Anas strepera), Pintail (Anas acuta), Shoveler (Anas clypeata) and Pochard (Aythya ferina). Six other species reach the same value in individual years.

The wet polders are also important for four types of Limikolen on the homeward journey and for the mountain pipit in winter.

A summary of the results of the water bird census from 1975 to 2015 was published in the Lower Oder Valley National Park Yearbook (KRUMMHOLZ 2016).

Table 1: Water bird census

Table 2: Water bird census

Table: Estimated maximum number of individuals of different bird species in the wetland of international importance (FIB) “Unteres Odertal” from the years between 1990 and 1996 (OAG Uckermark):

| Name | Quantity | Name | Quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common snipe | 300 | Teal | 4.720 | |

| White-fronted goose | 40.000 | Black-headed gull | 12.000 | |

| Pale rail | 7.100 | Shoveler | 3.000 | |

| Wood sandpiper | 500 | Wigeon | 8.000 | |

| Dark water strider | 45 | Tufted duck | 10.030 | |

| Goosander | 1.317 | Bean Goose | 28.300 | |

| Greylag goose | 700 | Golden blue duck | 1.381 | |

| Gray heron | 568 | Gadfly | 544 | |

| Greenshank | 118 | Whooper swan | 880 | |

| Great crested grebe | 95 | Pintail | 4.330 | |

| Mute swan | 800 | Mallard | 17.000 | |

| Ruff | 2.300 | Common gull | 7.000 | |

| Lapwing | 10.000 | Pochard | 12.300 | |

| Teal duck | 80 | Water pipit | 505 | |

| Cormorant | 563 | Dwarf slayer | 199 |

The Felchowsee and Landiner Haussee located in the Uckermark hills are also important resting areas for a number of water bird species, especially in summer and autumn when the wet polders are artificially kept dry, while the resting populations are only low in spring. The two lakes and the polder area complement each other seasonally in terms of their importance for migratory birds. The rapid pumping out of the water in the spring removes the resting opportunity for late-migratory species, the pumping operation in summer prevents the formation of wet spots and devalues the polders as a resting area at this time of the year and during the autumn migration. The pumping out of the flooded polders should be stopped as soon as possible from an ornithological point of view.

back to top![]()

Mammals

As part of these investigations for the care and development plan, only the small mammals were systematically recorded; In addition, voluntary individual examinations as well as the unpublished report of the Universities of Halle (Saale) and Osnabrück (SCHRÖPFER, R. & M. STUBBE 1996) were consulted.

In order to ensure a systematic qualitative recording of the small mammal population, 64 live traps were positioned in the area for three days and nights at eight locations. The 379 catches became ten species of small mammals plus the mouse weasel (Mustela nivalis) determined. In order of total frequency, these were wood shrews (Sorex araneus), Yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis), Bank vole (Clethrionomys glareolus), Nordic vole (Microtus oeconomus), Field mouse (Microtus arvalis), Firemouse (Apodemus agrarius), Harvest mouse (Micromys minutus), Water shrew (Neomys fodiens), Pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus), Mouse weasel (Mustela nivalis) and water vole (Arvicola terrestris).

The most species-rich areas were richly structured areas with various habitat elements such as reeds, tall perennials, woody plants and bodies of water, especially the softwood floodplains, which are rich in individuals. Areas that were periodically flooded were poor in individuals, unless higher areas offered appropriate retreats. Unused, moist grassland proved to be far more valuable in mammalian biology than hay meadows.

The Lower Oder Valley is of national importance for small mammals less because of the occurrence of threatened species than because of the large occurrence and high population density of demanding wetland dwellers such as the water shrew, the harvest vole and the Nordic vole, which has almost reached its western limit in the Lower Oder Valley.

The live catches were supplemented by the analysis of 224 trolls from 706 prey animals, which could be assigned to 622 small mammals. The bulbs came from tawny owl (Strix aluco) and barn owl (Tyto alba). The garden shrew (Crocidura suaveolens), Earth and house mouse (Microtus agrestis, Mus musculus) were only found in ridges, not in the live traps. The prey spectrum of the owls only partially corresponds to the composition of the small mammal community of the hunting grounds, for example the shrews are underrepresented in the tawny owl.

For wild boar (Sus crofa), Fallow deer (Cervus dama), Red deer (Cervus elaphus) and deer (Capreolus capreolus) the hunting statistics of the 13 hunting districts since 1992 were evaluated. However, several hunting districts extend far beyond the core area of the riparian strip program.

Wild boar (Sus crofa): 148 wild boars were shot in the 1994/95 hunting season, significantly fewer than in previous years. In the 2005/2006 hunting year, a total of 275 animals were shot in the national park. Wild boars can be found throughout the area, especially in some hillside forests, but also in dry polders and outside of the flood period in wet polders.

Wild boar

Fallow deer (Cervus dama): Two fallow deer were hunted in the 1994/95 hunting season, also fewer than in previous years. In the later years the number of hunted animals increased significantly, so in 2005/2006 a total of 38 and in the hunting year 2009/2010 a total of 22 animals were hunted. The main focus of fallow deer occurrence is currently the forests in the Schöneberg area.

Fallow deer

Red deer (Cervus elaphus): The red deer range is also low in the area and in the past few years had a maximum of 14 kills in the 2006/2007 hunting year. In the mid-1990s, the hunt for red deer was temporarily stopped. Forest damage caused by fallow deer or red deer plays only a minor role. In the course of the new hunting regulations in the national park, the red deer is no longer hunted in the polder areas, which means that depending on the flooding conditions, it populates these areas more or less constantly. Visitors to the Oder Valley can experience the rutting of the deer in Polder A near Criewen up close.

Deer (Capreolus capreolus): In the 1994/95 hunting season, 288 deer were shot, significantly fewer than in previous years. In the hunting year 2005/2006 the hunting distance was a total of 222 animals. To this day, experts do not agree on whether the current roe deer density is too high or perhaps even too low. The only thing that is certain is that the density of game is naturally subject to strong fluctuations. According to new theories, it should be the traditional, natural role of the herbivorous game to keep clearings in the natural forest open for those species that we know today only as cultural followers. In any case, the deer can be easily observed today in the Lower Oder Valley, especially in the polder areas that can be seen from the dike tops. Due to the hunt for deer, which has existed for a number of years, the animals are sometimes very familiar with visitors to the National Park.

Fawn

Moose (Alces alces): Although the elk is not hunted, it should be briefly introduced in this context as a large game that can be hunted. It was exterminated in this area in the Middle Ages. In the past, however, moose have repeatedly been observed roaming the area. It is to be expected that the elk will be permanently at home in the newly created wilderness areas in the Lower Oder Valley. He could become a symbolic animal. An elk settlement near Warsaw resulted in a stable elk population in central Poland. The moose migrating westwards probably come from this population. Frequent feeding areas for the immigrated animals are floodplains, forest areas and swamps rich in ponds and lakes, as well as areas rich in softwood in other locations that have a favorable food supply (Heyne 1996).

Moose

Brown hare (Lepus europaeus): Although the brown hare has become increasingly rare in Brandenburg, it is still one of the most common mammals in the Lower Oder Valley. It populates the dry grass slopes as well as the polder area and the surrounding arable landscape, in the arable landscape near Gartz in a density of around ten specimens per 100 ha. Wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), on the other hand, are now probably extinct in the Lower Oder Valley.

Hare

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes): The red fox is also very common in the Lower Oder Valley. Especially during floods, it can be seen on the dykes, where it retreats just like its prey. Since the rabies vaccination, the foxes have been able to reproduce strongly in the Lower Oder Valley as well as in the whole of Brandenburg. 130 of them were shot in the 1994/95 hunting season. Due to the hunting regulations of the national park, there is no longer any regulation of the population. The stocks fluctuate because in some years diseases such as z. E.g. the mange that affects density.

Fox

Raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides): The raccoon dog, originally native to East Asia, has also become naturalized in the Lower Oder Valley. In the years 1996/97, 13 copies were collected as road traffic victims. Since it feeds on birds and their eggs, among other things, it can — like the fox — be dangerous for meadow breeding populations, which are polluted in many ways. These predatory mammals would not pose a risk for the meadow breeders under natural conditions; they would be given in particular if the grassland is cultivated very extensively and the summer pumping operations for the artificial drainage of the polders are discontinued.

Racoon (Procyon lotar): The small bear, originally from North America, was released into the wild in Hesse before the last world war to “enrich” the fauna and the animals that escaped from a fur farm on the outskirts of Berlin in 1945 conquered large parts of Germany in the last few decades. The national park has also been inhabited for two decades, initially only by individual animals. Especially in the southern part of the protected area, north to Schwedt / Oder., It is widespread today. Due to its predominantly nocturnal activity, it is rarely observed. Due to his skills, he is a good climber and likes to swim, he regularly plunders the colonies of herons and cormorants as well as the seagulls.

Racoon

Two species of mammals are particularly typical of the Lower Oder Valley:

Otter (Lutra lutra): Evidence and mapped traces of the otter can be found all over the polder area. The majority come from larger oxbow lakes in the polder area, which are favorable otter habitats due to their structural richness. Most of the evidence, mainly through the solution and marking and feeding places, can be found in the Criewener, Schwedter and Fiddichower as well as in the Friedrichsthaler polder. But traces were also found in the Oder foothills of Lunow and Stolpe. The Lower Oder Valley, with its multitude of bodies of water and its uncut large area, is likely to be an outstanding settlement area for otters. Connections with occurrences in the Salveybach, the Randow-Welse-Bruch and the Felchowsee area as well as to the Polish side are to be assumed. Proof of reproduction is available almost every year through observation of young leading females. Road traffic also repeatedly claims victims, especially on the B 2 between the Mühlenteich in Gartz and the Westoder, as well as on the former B 2 at Zützen — Meyenburg.

Otter

Beaver (Castor fiber): In the Lower Oder Valley, the beaver was exterminated in the 18th century. In order to reintroduce citizenship, Elbe beavers were released in northeast Brandenburg in the 30s and 70s of the 20th century, to which all present-day occurrences can be traced back. The first more recent records come from Mescherin in 1967, from the area around Stettin (Szczecin) in 1971, from Friedrichsthal in 1982 and from the Salvey valley in 1984. However, these observations and findings of interfaces were more likely to be traced back to individually migrating animals than to permanent settlements. The beaver has been down-to-earth in the Zwischenoderland near Gartz and Mescherin since the early 1990s, and in the Fiddichower Polder since the mid-1990s. The species currently inhabits practically all bodies of water in the national park, including the small, only periodically water-bearing ditches in the hillside forests, where it dams the water through dams. Approximately 80 settlements are currently expected in the area. Subspecies such as the Elbe beaver (C. f. Albicus) and the Eastern European beaver who immigrated from Poland (C. f. Vistulanus) on. Both subspecies mate and then form hybrids.

Swamp beaver

A total of 58 mammal species have so far been recorded in the Lower Oder Valley, some of which such as the elk and wolf (Canius lupus) are not yet down to earth and the gray seal (Halichoerus grypus) was proven for the first time for the state of Brandenburg. The down-to-earthness of some bat species is also questionable; the evidence relates to nocturnal hunting in the national park. This means that more than half of the 101 mammal species in Germany and more than two thirds of the mammal species recorded in Brandenburg are found in the Lower Oder Valley. 23 of them are on Brandenburg’s Red List as threatened or even extinct, 10 on the list of the Federal Republic of Germany. For such a small area (0.3% of the area of Brandenburg) that is a remarkable quotient.